Many organizations have a set of corrugated cartons, a regime, used as shippers. These regimes range from a few sizes to many with various dimensions and grades. Just what the dimensions are greatly impacts a variety of costs—material, warehousing, and freight. Importantly, customers’ perceptions are shaped by our packaging when, for example, they open their cartons and discover 70% of the contents are air or dunnage. That risks customers switching to “greener” competitors and criticism on social media.

There’s a way to design a carton regime that addresses both costs and Volume utilization. Smart regime designers save 20% or more of their costs and impress customers with their packaging skills.

THE BIG PICTURE

Corrugated Shippers might be just one component of your packaging arsenal. We’ll focus on corrugated carton regimes, RSCs, Regular Slotted Cartons, made from corrugated fiberboard.

We’ll look at the number and the dimensions of the cartons an organization should have in its regime. We’ll quantify the problem, apply several techniques and illustrate how an organization can design its own high-quality low-cost-regime.

To start let’s frame the high-level problem. Suppose you started with a regime of 10 RSCs and wanted to specify the dimensions of each one. Well, each carton has three dimensions, Length, Height and Width. They can have many values usually confined by carton suppliers to 8th inch increments. Each dimension, varying from, say, a minimum of 5 inches up to, say, a maximum of 30 inches, could take on 200 values ( (30-5) * 8 ). Since each of the 30 dimensions can be selected independent of all the others, there are 30^200 options for the 10-carton regime. Then there’s the 11-carton regime to consider. Wow!

These are astronomically high numbers. It is not possible to evaluate every option. If it took just one-trillionth of a second to evaluate an option (Cray computer-like speed), evaluating all those options would still consume more time than has taken place since the Big Bang. So, any approach that evaluates regime options must pair these numbers down radically. Fortunately, there are ways to do just that.

THE GENERAL APPROACH

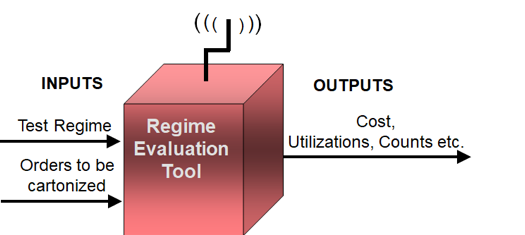

Designing a carton regime requires an evaluation procedure, a Tool, that, for a particular regime, calculates its costs. It would look like this

For a set of orders, say a year’s worth, the Tool would calculate the cost of any input “Test” regime. By varying the Test regime, we could pick the one that bore the lowest costs.

Costs driven by your carton regime generally have three components—the corrugated material, warehousing and freight. The material cost is the amount paid to the carton supplier—typically a corrugator in higher Volume situations and a distributer otherwise. Warehousing should include the cost to maintain the carton inventory and the labor to manually package the odd orders not containable by the regime. Freight might include multiple elements such as weight, number of cartons on the orders and Dimensional Weight charges.

All Carton regime design efforts follow this approach. Importantly it is possible (and desirable) to construct a Tool that varies the Test Regime by itself rather than require human intervention to construct new Test regimes each time.

DESIGN SPECIFICS

Techniques you can apply to design your regime include:

Volumetric Need

The purpose of a carton regime is to “contain” orders. Containment is best measured by Volume. It’s not the number of orders, their weight or their value, rather the resource that is consumed by containing customers’ orders is the Volume of the cartons needed to ship those orders. Understanding this Volumetric Need helps apply important physical design specifics.

Optimal Cartons

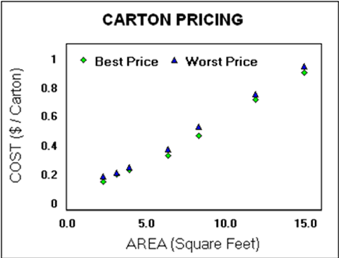

RSCs are erected from blanks. That blank has a specific area. The material cost portion of a carton, for the Kraft paper used to construct it, is proportional to this area. Moreover, cartons are made on a large expensive corrugating machines that have limited capacity. Cartons use that capacity in proportion to their area. Area drives other carton making costs too—slotting, scoring, printing, folding. So, it’s natural that RSCs costs are proportional to the area of the blacks they are made from.

You can confirm that cost is proportional to area with your own current regime. The area of the unfolded blank of an RSC is 2 * (Height + Width) * (Length + Width). Contemporary costs for simple cartons from a corrugator sold to a reasonably high-volume customer usually range between 6 and 8 cents per square foot. Check out your cost-Area pattern. It should look something like this:

“Optimal” cartons use the least amount of corrugated area per Volume. And because RSC costs are proportional to their area, optimal cartons are the lowest cost per Volume too.

“Optimal” cartons use the least amount of corrugated area per Volume. And because RSC costs are proportional to their area, optimal cartons are the lowest cost per Volume too.

This cost to Area proportionality means that we can derive the dimensions of optimal cartons—just maximize Volume / Area, or, equivalently, minimize the Area / Volume. Doing the math results in the discovery that optimal cartons have Length, Height, Width ratios of 2 to 2 to 1. (Clearly the old adage “deeper is cheaper” has its limits.) So, any carton with these ratios is optimal, it has the most Volume for that Area (or cost) and the lowest cost (or Area) per Volume.

As a first step your regime can be designed with optimal 2, 2, 1 cartons. While there may be reasons to deviate from these ratios, doing so will add material cost to your regime.

Volumetric Balancing

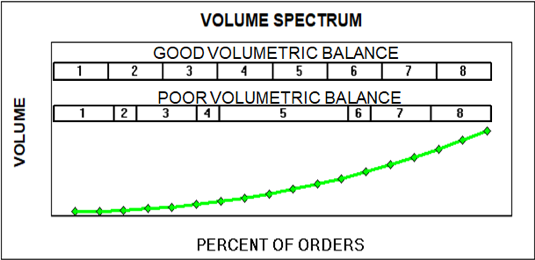

A next step in the design of a regime might be to apply the “Volumetric spectrum” test. A regime will consist of a specific number of cartons—6, 7, 8, so on. Each carton will have to be inventoried and managed as an item to be stocked, reordered, received, and put-away periodically. So, each carton will have to “bear its weight” in the regime—make its contribution. It will do so by being selected to contain a balanced portion of the Volume spectrum, the array of Volumes of all customers’ orders, our key resource. Accordingly, a given carton should not cover a very small nor a very large part of that Volume spectrum.

The following illustrates the point in an 8-carton regime:

Cartonization Specifics

Cartonization Specifics

In higher Volume organizations individual Items of an order are assigned to specific cartons before being released to a warehouse for fulfillment. This process typically occurs in a WMS or other order processing system. The Tool used to evaluate any carton regime will have to mimic the assignment algorithm embedded in your order processing system.

Knowing how the assignment process works will help design the best regime. Actually, there is a subtle feedback process between Item assignment and carton design; investigating one leads to improvements in the other.

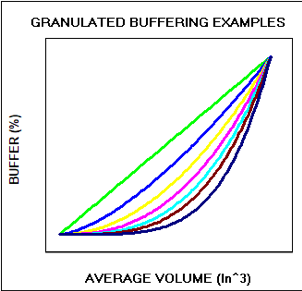

For example, many assignment processes employ a Volume “buffer” often set to 15%. It’s applied by limiting the Volume of Items assigned to a carton be less than 85% of that carton’s actual Volume. This approach is a crude way of accounting for items not nesting perfectly in a carton. (This buffer is not applicable to one-Item orders, a situation you might check-up on in your own assignment procedure.)

If you have buffers, you could apply “Granulated Buffering”. This approach exploits the fact that more granular orders, ones with many small items, need less buffering than orders with few large items; think sand versus rocks. Here’s an illustration of the potential relationships

This approach has a double benefit. It assigns smaller buffers to “sandy” orders and it reduces the costly repacking needed at packing stations when “rocky” orders won’t fit their assigned too-smaller cartons.

This approach has a double benefit. It assigns smaller buffers to “sandy” orders and it reduces the costly repacking needed at packing stations when “rocky” orders won’t fit their assigned too-smaller cartons.

In the other direction, knowing the assignment algorithm leads to better regimes. For example, a common approach assigns items to a carton if they are Volumetrically compatible and have their longest dimension less than the length of the carton. In this case your carton design options can concentrate on just Volume and Length, two elements rather than three.

MOUNTAIN CLIMBING IN THE DARK

Designing a carton regime is like climbing a mountain range blindfolded. We test a regime by evaluating it with the Tool—taking a step in the mountain range. We will have saved more if costs decrease—if we have climbed higher up the hill we’re on in the mountain range. Because we cannot tell which step to take until after we take it, we are blindfolded. Our step, our Test regime, is a “stab in the dark.”

This makes the design process challenging and interesting. To climb the mountain, we must make good steps—construct cost reducing Test regimes. Effective approaches make smart steps in the mountain range. They automate the Test regime construction process for speed, they gauge the “lay of the land” to tell which way is up. They avoid going down valleys and strive to go up steep slopes. They recognize if you are on a global peak or if there’s higher ground somewhere else in the range. And they do all this quickly with available computer resources.

Having a smart automated process will design cost-effective regimes quickly, save costs and help retain customers.