Schneider revamps intermodal service on U.S.-Mexico corridor

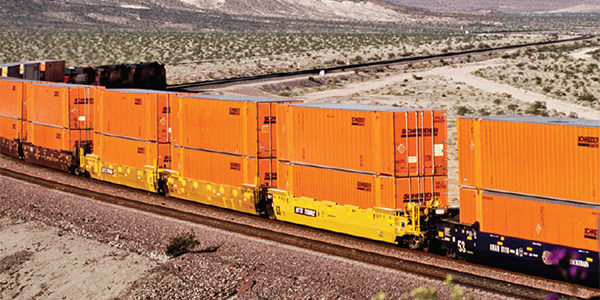

Truckload and logistics giant Schneider National Inc. said it has revamped its U.S.-Mexico intermodal service to shave a day from transit times on the high-potential but still-underutilized corridor.

The restructured offering, which began earlier this month, replaces Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway with Canadian National Inc. (CN) on the critical node linking the U.S. southern tier with Chicago and points beyond, according to Jim Filter, Schneider's senior vice president, intermodal sales and marketing.

On a northbound move under the old service, Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway would transport Schneider containers from Mexico to Rosenberg, Texas, outside of Houston. From there, the equipment would be placed on a truck and drayed to BNSF's intermodal ramp in Pearland, Texas, about 40 miles away. Then BNSF would haul the goods to Chicago for distribution.

Under the new service, KCS links with CN at the Canadian railroad's node in Jackson, Miss. There, CN carries the freight to Chicago for distribution, according to Filter.

The rail-to-rail link eliminates the time required for off-loading the cargo to a truck for the trip between the KCS and BNSF terminals, Filter told DC Velocity yesterday at the joint annual conference of the National Industrial Transportation League (NITL), the Intermodal Association of North America, and the Transportation Intermediaries Association in Houston. The link also reduces the scheduling variability that often comes with depending on a dray to deliver goods between rail points, he said.

The service is being used for intermodal loads moving in both directions, Filter said.

THE GROWING INTERMODAL ADVANTAGE

Schneider, based in Green Bay, Wis., has served the U.S.-Mexico intermodal market for years. The newly

revamped service is an effort to tap into intermodal's value in one of the world's fastest-growing trade lanes.

Intermodal containers travel in-bond and clear customs at the destination rail ramp. As a result, intermodal users

bypass the massive truck congestion at border crossings. Shipping by intermodal also avoids the time-consuming scenario

of handing off trailers to different drivers at the border.

In addition, intermodal theft is virtually nonexistent because the doors of the lower-container on a double-stack train cannot be opened while in the well car and the upper container is more than 15 feet off the ground.

Still, only 5 percent of cross-border truck service that could be converted has actually shifted, Filter said. Intermodal "should be growing much faster than it is," he said.

Intermodal accounts for about 30 percent of privately held Schneider's $3.5 billion in annual revenue. It has become an increasingly larger component of Schneider's overall product mix, Filter said.

A good chunk of intermodal's growth is coming from traffic that once moved over the highway but has now been converted to rail. About one-quarter of Schneider's new intermodal business from shippers involves an over-the-road conversion, according to Filter.

The modal shift has intensified in the past two or three years as shippers and trucking companies themselves confront a range of issues from highway congestion to a shortage of qualified drivers to escalating fuel, labor, and truck equipment costs. Those elements have only amplified intermodal's traditional cost, fuel, and environmental advantages.

Intermodal has a 9.5-percent market share of domestic dry van-type movements moving 550 miles or longer, according to FTR Associates, a freight analysis company. That represents a 0.1-percent increase per calendar quarter during the past two years, it said.

Intermodal is still used mostly for long-haul movements. The average intermodal haul is about 1,430 miles, though the distance is decreasing, according to FTR data. The overall length-of-haul is skewed by long-distance moves from the West Coast to the Midwest where there aren't many big population centers in between. However, in the more densely populated Eastern half of the United States, railroads are operating intermodal service at lengths of haul between 550 miles and 750 miles and are doing so with a greater degree of reliability. Most of intermodal's growth, and its greatest potential, lies in the shorter-haul traffic lanes in the East, according to experts at the NITL conference.

For example, Filter said Schneider regularly uses intermodal between Chambersburg, Pa., and Chicago, a distance of about 700 miles. Its primary Eastern rail partner for intermodal, CSX Transportation, a unit of CSX Corp., performs the run with a high degree of reliability, he said. Because the railroads' investments in infrastructure and equipment, they are doing a better job on shorter-haul lanes. As a result, Schneider is pushing for more traffic moving under 1,000 miles to go by intermodal.

About 15 percent of truck freight in the Eastern half that could be converted to intermodal has shifted that way, Filter said.

Anthony B. Hatch, a long-time rail analyst and currently head of a transport consulting company that bears his name, predicted at the conference that increased intermodal traffic will spark a second "rail renaissance." Hatch said the first so-called renaissance began in 2004 as the carriers wrested pricing power from shippers and rail service levels started to show significant improvement.

Hatch said private and publicly held railroads will devote more of their enormous capital expenditures on track and equipment—which are expected to reach $13 billion by the end of 2013—to intermodal. Hatch added that intermodal will receive even more focus as the railroads scale back investments in their coal transportation business, which still generates the biggest share of overall revenues. Coal demand has been hurt by competition from lower-cost, cleaner burning natural gas and government environmental regulations that have discouraged electric utilities from building coal-fired plants or maintaining and upgrading existing ones.

Related Articles

Copyright ©2024. All Rights ReservedDesign, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing